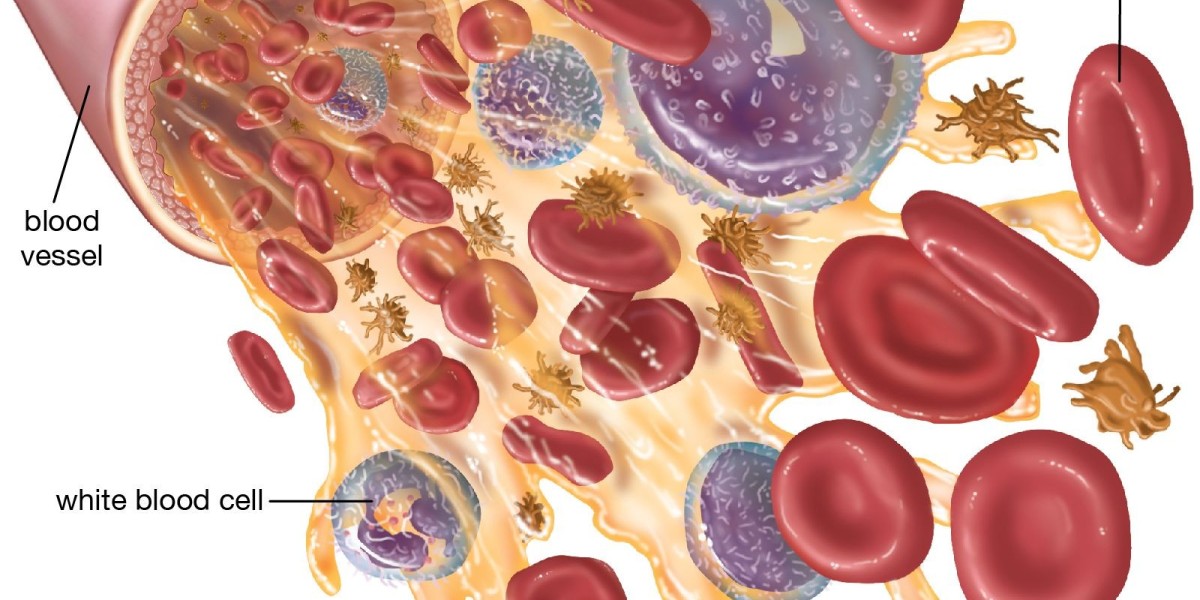

White blood cells, also known as leukocytes, are central components of the human immune system and serve as the body’s primary defense against infectious agents, foreign substances, and abnormal cellular activity.

Although they constitute less than 1 percent of total blood volume, their functional significance far outweighs their proportion. White blood cells originate primarily in the bone marrow and circulate through the bloodstream and lymphatic system to monitor for pathological threats.

They can be broadly classified into five major types: neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils. Each subset exhibits distinct structural, biochemical, and functional characteristics that enable a coordinated and highly adaptive immune response.

Understanding these cell types provides meaningful insight into immune system behavior, diagnostic interpretation, and therapeutic decision-making.

This is also an area of high relevance within pharmaceutical distribution, where stakeholders such as a ceftriaxone injection wholesaler may focus closely on infection-related clinical patterns that influence antimicrobial utilization.

Neutrophils

Neutrophils constitute the largest proportion of circulating white blood cells, typically accounting for 50 to 70 percent of the total leukocyte population. They are the first responders to microbial invasion, especially in the context of acute bacterial infections.

Neutrophils recognize chemotactic signals emitted from damaged tissues or pathogens and rapidly migrate to the affected site in a process known as diapedesis. Their defensive mechanisms include phagocytosis, degranulation, and the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).

During phagocytosis, neutrophils engulf and enzymatically degrade bacteria and debris, using lysosomal enzymes and reactive oxygen species. Degranulation involves the release of antimicrobial peptides and proteolytic enzymes that directly compromise pathogen integrity.

NETs, composed of chromatin and granule proteins, immobilize and neutralize microorganisms extracellularly. Due to their rapid turnover and high energy demand, neutrophils have a relatively short lifespan often less than 24 hours yet their collective action is indispensable for front-line immune protection.

Lymphocytes

Lymphocytes form the second-largest group of white blood cells, typically comprising 20 to 40 percent of the leukocyte count. They provide highly specialized and adaptive immune responses. The primary subtypes include B cells, T cells, and natural killer (NK) cells.

B cells are responsible for humoral immunity. Upon activation, they differentiate into plasma cells that synthesize antigen-specific antibodies. These antibodies neutralize pathogens, facilitate opsonization, and support complement activation. Memory B cells provide long-term immunity by enabling rapid antibody production upon re-exposure to the same pathogen.

T cells mediate cellular immunity. Helper T cells (CD4+) coordinate immune responses by releasing cytokines that activate other immune cells. Cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) target and destroy virus-infected or malignant cells. Regulatory T cells help maintain immune tolerance and prevent excessive immune activation that could damage host tissues.

NK cells are part of the innate immune system but function with a level of specificity. They identify cells lacking normal major histocompatibility complex (MHC) markers, a feature common in virally infected and cancerous cells, and induce apoptosis through perforin and granzyme pathways.

Collectively, the lymphocyte population ensures immune adaptability, specificity, and long-term protection.

Monocytes

Monocytes represent approximately 2 to 8 percent of circulating leukocytes and serve as precursors to macrophages and dendritic cells. They circulate in the bloodstream for several days before migrating into tissues, where they differentiate based on environmental cues.

Macrophages perform phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and cytokine secretion. They are essential for clearing pathogens, apoptotic cells, and cellular debris. Their antigen-presenting capabilities bridge innate and adaptive immunity by delivering pathogen-derived antigens to T cells.

Dendritic cells are among the most potent antigen-presenting cells. They capture antigens in peripheral tissues and migrate to lymphoid organs to activate naïve T cells. This activation is foundational to initiating adaptive immune responses.

Monocytes also play a critical role in inflammation and tissue repair. They release pro-inflammatory cytokines during infection and contribute to wound healing through extracellular matrix remodeling and angiogenesis support.

Eosinophils

Eosinophils typically account for 1 to 4 percent of white blood cells and are best known for their role in combating parasitic infections and mediating allergic responses. Their cytoplasmic granules contain major basic protein, eosinophil peroxidase, and other toxic enzymes used to degrade parasites and helminths too large for phagocytosis.

Beyond antiparasitic activity, eosinophils participate in the regulation of inflammation. They release cytokines, chemokines, and lipid mediators that modulate the activity of other immune cells. Elevated eosinophil levels (eosinophilia) are frequently associated with asthma, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and certain autoimmune conditions.

Basophils

Basophils are the rarest of all white blood cells, accounting for less than 1 percent of the total population. Despite their rarity, they play a crucial role in allergic and hypersensitivity reactions. Basophils contain granules rich in histamine, heparin, and various cytokines.

Upon activation, basophils release histamine, which increases vascular permeability and smooth-muscle contraction, contributing to the manifestations of allergic responses such as urticaria and bronchoconstriction. They also release leukotrienes and interleukins that amplify inflammatory pathways. Basophils are functionally related to mast cells, although mast cells reside primarily in tissues rather than circulating in blood.

Integrated Immune Function

Although each white blood cell type performs distinct functions, their activities are interconnected. An infection may activate neutrophils for immediate response, monocytes/macrophages for sustained phagocytic activity and antigen presentation, and lymphocytes for targeted and long-lasting immunity. Eosinophils and basophils contribute to pathogen defense and inflammatory modulation, particularly in parasitic and allergic contexts.

Clinically, differential white blood cell counts are essential diagnostic tools. Increased neutrophils often indicate bacterial infection, while elevated lymphocytes suggest viral etiologies. Eosinophilia can signal allergic disease or parasitic infection.

Understanding these patterns helps guide therapeutic decisions, including antimicrobial selection. For example, in healthcare supply chains, trends in infection-related diagnoses influence purchase volumes for antibiotics, which is relevant for stakeholders such as a ceftriaxone injection wholesaler monitoring demand patterns across hospitals and clinics.

Conclusion

White blood cells are vital to the body’s defense mechanisms. Their diversity enables the immune system to respond to a wide range of threats with both speed and precision. Neutrophils provide rapid protection, lymphocytes offer specificity and memory, monocytes support sustained and integrative immunity, and eosinophils and basophils contribute to specialized defensive and inflammatory processes. A clear understanding of these cell types and their interactions is indispensable in clinical practice, diagnostics, and therapeutic planning.